With the success of the Cleveland Guardians this season, fans are dreaming of October baseball.

With the success of the Cleveland Guardians this season, fans are dreaming of October baseball.

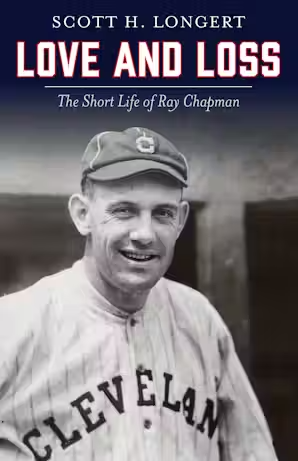

It’s the perfect time for a visit from renowned baseball historian Scott Longert, author of half a dozen books about professional baseball in Cleveland, including his latest – Love and Loss: The Short Life of Ray Chapman.

[READ MORE ABOUT SCOTT LONGERT]

Longert will visit Rodman Public Library at 6:30 p.m. on Monday, October 7 as part of the 2024 Fogle Author Series to discuss his new biography about the Cleveland Indians shortstop who holds the distinction of being the only player to die directly from an injury received on the field during a Major League baseball game.

Registration is required to attend Longert’s visit.

Chapman was in his eighth season with Cleveland on August 16, 1920 when he was struck in the head by a pitch at the Polo Grounds in New York City by Yankees pitcher Carl Mays, who had dirtied the ball. Mays threw the discolored ball with a submarine delivery in the late afternoon shadows, and presumably, all those factors combined made it difficult for Chapman to see.

In fact, eyewitnesses say that Chapman never reacted to the pitch. Reports said the sound was so loud when it impacted with Chapman’s skull, that many thought it had made contact with his bat, including Mays, who actually fielded the ball and threw it to first base.

Bleeding from his ear, Chapman tried to walk off the field, but his knees buckled. He was taken to St. Lawrence Hospital, just a short distance from the field. Despite emergency surgery to relieve swelling on his brain, Chapman died in the early morning hours the next day.

He left a grieving, pregnant wife of less than a year, his teammates who went on to win the World Series that year, and many fans and friends – counting among those Ty Cobb, a person who counted very few fellow players among his pals.

Am ong the best at his position during his time, Chapman led the American League in runs scored and walks in 1918. A top-notch bunter, Chapman is sixth on the all-time list for sacrifice hits and holds the single season record with 67 in 1917. He batted .300 or better three times, and led the Indians in stolen bases four times. In 1917, he set a team record of 52 stolen bases, which stood until 1980. He was hitting .303 with 97 runs scored when he died.

ong the best at his position during his time, Chapman led the American League in runs scored and walks in 1918. A top-notch bunter, Chapman is sixth on the all-time list for sacrifice hits and holds the single season record with 67 in 1917. He batted .300 or better three times, and led the Indians in stolen bases four times. In 1917, he set a team record of 52 stolen bases, which stood until 1980. He was hitting .303 with 97 runs scored when he died.

Despite dying at such a young age, he has left an enduring impression on baseball.

His death led to rules requiring umpires to replace the ball whenever it becomes dirty and led to the ban on spitballs after the 1920 season. Chapman's death was also one of the examples cited to justify the wearing of batting helmets, although it took more than 30 years to adopt the rule that required their use.

Acclaimed for his deep dives in Cleveland baseball history, Longert said his fascination with Chapman began with his visits to the baseball icon’s final resting place in Lakeview Cemetery. Visitors leave balls, bats, and gloves at the grave, a tribute to Chapman and his influence on the sport.

While many know the story of Chapman’s tragic end, Longert also wanted to tell the entire story of Chapman’s brief life, which he says was marked by tremendous highs and devastating lows, offering lessons in resilience and the fleeting nature of success.

While he was in his prime, Chapman had indicated that 1920 was to have been his last season. His widow, Kathleen Daly Chapman, was the daughter of a prominent businessman. The couple wed shortly before the start of the season and Chapman had planned to devote himself to starting a family and the business into which he had married.

But Chapman’s life was cut short and those plans were shattered by one pitch.

Ahead of his visit to Rodman Public Library, Longert shared some insights into his career and writing process. Here’s what he had to say:

Q: You’ve had some interesting positions with a history bent. Can you talk a little bit about your varied positions as a park ranger at the James A. Garfield Site, at Shandy Hall, and as sports archivist for the Western Reserve Historical Society.

A: I have always had a dual interest in American history and baseball history, although the two do intersect. Working at Western Reserve got me the opportunity to do both. Shandy Hall is the 19th century home of Col. Robert Harper, a veteran of the War of 1812. I was fortunate to serve as site manager for the summers, and during the winter, manage the sports archives at WRHS. Around 2007, WRHS decided to turn over President Garfield’s home to the National Park Service which created a need for park rangers. Since I was familiar with the site, I was selected to be a ranger which was quite an honor. In my time there, I started a Civil War encampment to honor General Garfield and I presided at the naturalization ceremonies each July and September.

Q: What got you interested in baseball history and how did you get your start writing about it?

A: When I was a child, I received a copy of a book titled The Glory of Their Times by Lawrence Ritter. A series of interviews with men who had played professional baseball at the turn of the 20th century. I was fascinated by it, particularly their recollections about Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson, and after graduation from college, I began to study the subject seriously. I submitted several freelance articles, and after several years, I got published. That spurred me on to continue researching and writing, with full length manuscripts a few years later.

Q: Did you always want to be a writer?

A: Not until I graduated college and had a day job. I then knew I could write on evenings and weekends and would not starve.

Q: What made you decide to write about Ray Chapman?

A: Many people knew about Ray and that he was killed by a pitched ball in 1920, but few knew anything about his life, which was an exceptional one. I believed the public would be interested in learning about him and all he accomplished before he died. He had a fairytale romance with a wealthy socialite which I am sure book buyers would enjoy reading. Plus he was a great shortstop, one of the best in my opinion.

Q: Can you talk a little bit about your research process and your writing process for the book?

A: I do all my research before I begin to write, including player’s files from the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Newspaper research, periodicals and interviews with family members, if possible. I then sketch out chapters and how they should be framed, then it’s about a year of writing and rewriting.

Q: What do you hope people take away from the book?

I hope people will learn what an extraordinary person Ray was and how he conducted his life up to his death. He was kind, considerate and a great storyteller, which endeared himself to many folks both ballplayers and non. He loved children and gave baseballs out to the kids who stood outside League Park in Cleveland because they could not afford admission to the games or the price of a ball.